zaterdag 27 juli 2024

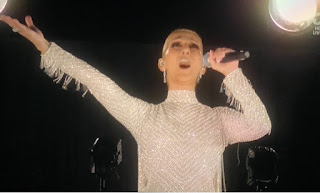

Celine Dions opening

Het absolute hoogtepunt van de opening van de Olympische Spelen in Parijs. Een opening in een opening. Haar optreden was een opening in zichzelf. Tegelijkertijd subliem en eenzaam. Ze torende letterlijk en figuurlijk boven alles en iedereen uit.

Labels:

Celine Dion,

Olympische Spelen,

Parijs

maandag 15 juli 2024

A refined version of the argument for God’s existence from non-bruteness

In what follows, I present a refined version of my recently developed argument for God's existence from non-bruteness. The argument deploys possible worlds. Possible worlds represent different ways the world could have been, encompassing all variations of how reality might manifest. Each possible world w has a fundamental metaphysical structure, denoted by S(w), and two possible worlds can share the same fundamental structure. Possible world w1 is accessible from possible world w2 if and only if there exists a relation between w1 and w2 such that any state in w1 can be accessed from w2. I assume that accessibility is a symmetric relation, meaning that if possible world w1 is accessible from possible world w2, then w2 is equally accessible from w1.

In what follows, I present a refined version of my recently developed argument for God's existence from non-bruteness. The argument deploys possible worlds. Possible worlds represent different ways the world could have been, encompassing all variations of how reality might manifest. Each possible world w has a fundamental metaphysical structure, denoted by S(w), and two possible worlds can share the same fundamental structure. Possible world w1 is accessible from possible world w2 if and only if there exists a relation between w1 and w2 such that any state in w1 can be accessed from w2. I assume that accessibility is a symmetric relation, meaning that if possible world w1 is accessible from possible world w2, then w2 is equally accessible from w1.Perspectives refer to the points of view or standpoints from which a possible world can be experienced or understood from within. They encode cognitive capabilities and epistemic positions. Let M be a function that maps each possible world to a set of perspectives accommodated by that world. A possible world w accommodating perspective P does not necessitate the existence of an individual in w adopting P. Moreover, the same perspective can figure or be present in multiple possible worlds, necessitating a notion of identity of perspectives across possible worlds. I assume the existence of an adequate notion of transworld identity of perspectives. Thus, some essential feature or set of features of perspectives allows the same perspective to exist across different possible worlds. Traditionally, transworld identity addresses the question of whether an entity or structure in one possible world is the same in another. Transworld identity of perspectives is closely related to that of entities and structures. A perspective in a possible world can be either unlimited or limited. An unlimited perspective in a possible world is an unrestricted, all-encompassing viewpoint, allowing a complete understanding of all aspects of that world. For example, the human perspective in this world is reasonably a limited perspective.

A proposition can only be self-evident if it can possibly be recognized as such. This necessitates the following conceptual analysis of self-evidence. A proposition p is self-evident in possible world w from perspective P if and only if P is in M(w) and in every possible world w' that is accessible from w, and that is sufficiently similar to w (i.e., is such that M(w')=M(w) and S(w')=S(w)), an individual adopting perspective P in w' and contemplating p immediately recognizes it as true without the need for further explanation, while there is at least one possible world w'' accessible from w and sufficiently similar to w in which an individual exists who adopts perspective P in w''. The clause requiring that there must be an accessible and sufficiently similar possible world in which the relevant perspective is adopted, prevents a proposition from being self-evident merely because there is no accessible and sufficiently similar possible world in which the perspective in question is adopted. This clause thus avoids a misguided conception of self-evidence. The relation E(p,w,P) denotes that p is self-evident in w from perspective P.

Let S be the fundamental structure of the actual world a. The core premise of my argument asserts that it is not a brute fact that S is the fundamental structure of a; hence, there must exist an ultimate reason in a for S being the fundamental structure, denoted by proposition r. As an ultimate reason, r not only renders it likely that S is the fundamental structure but also entails that S is the fundamental structure. Proposition r, as an ultimate reason, must terminate any regress of explanations. Therefore, there is an unlimited perspective U in a such that E(r,a,U).

According to the definition of self-evidence, there exists a possible world w2, accessible from the actual world, such that S(w2)=S(a)=S, and there exists an individual i in w2 who has perspective U in w2 and contemplates r, immediately recognizing r as true without the need for further explanation. This means that individual i recognizes E(r,w2,U). Additionally, i recognizes that r entails S is the fundamental structure. Hence, i recognizes r as the ultimate reason for S being the fundamental structure.

Individual i has an unlimited and therefore wholly independent or absolute perspective in w2. Hence, specifically, i is uncaused and thus exists by virtue of its own nature in w2. It follows that i exists necessarily in w2. Therefore, i exists in all possible worlds accessible from w2, including the sufficiently similar actual world. Thus, there is an individual in the actual world with an unlimited perspective, who is uncaused or first, and who recognizes r as self-evident and as being the ultimate reason for S being the fundamental structure.

A proposition p is self-evident in an absolute sense if and only if for all possible worlds w, there exists an unlimited perspective P in w such that E(p,w,P). Now, r must be self-evident in an absolute sense. I will demonstrate this. If r were not self-evident in an absolute sense, there would exist a possible world w* in which there is no unlimited perspective U* such that E(r,w*,U*). If the fundamental structure of w* differs from S, an additional explanation for S being the actual fundamental structure would be necessary — namely, why w* is not actual, thereby preventing S from being the actual fundamental structure. This contradicts r terminating the regress of explanations. If the fundamental structure of w* is S, it still follows that if w* were actual, r would not terminate the regress of explanations due to a lack of an unlimited perspective U* in w* such that E(r,w*,U*). Again, an additional explanation of why w* is not actual would be required, preventing r from being an ultimate reason.

Thus, there exists an individual in the actual world with an absolute perspective, who is uncaused or first, who recognizes r as self-evident in an absolute sense, and who also recognizes r as the ultimate reason for S being the fundamental structure of the world. Given parsimonious considerations, we may reasonably assume there is one such individual unless there are good reasons to believe otherwise. This individual is properly referred to as God. Hence, God exists.

The first premise of my argument is the non-bruteness premise. One may reject this premise, of course. That is to say, one may not accept that there must be some ultimate explanation of why the world has the fundamental structure it has. Yet, the argument shows that to the extent it is plausible that there is such an ultimate explanation, it is plausible that God exists. Many believe that such an ultimate explanation plausibly exists. What my argument demonstrates is that if there is such an ultimate explanation, theism is true. Thus, the argument effectively rules out non-theistic ultimate explanations of the world's fundamental structure. If my argument is successful, the atheist must maintain that there is no ultimate explanation for why the world has the fundamental structure it has, which for many atheists may not be a desirable position to hold.

dinsdag 9 juli 2024

Wittgensteins Tractatus en het semantisch argument

Gisteren besprak ik uitgebreid mijn semantisch argument met Joop Leo van de afdeling Formal Semantics & Philosophical Logic van het Institute for Logic, Language and Computation in Amsterdam. Het was een mooi gesprek waarbij naast mijn semantisch argument ook de Tractatus van Wittgenstein de nodige aandacht kreeg. Zo besprak ik mijn eerder op dit blog uitgewerke interpretatie van Wittgensteins voorwerpen en atomaire feiten. Leo stelde vervolgens een fascinerend tegenvoorbeeld tegen het identiteitscriterum van mijn semantisch argument voor. Beschouw de concepten 'Aangetrokken worden door de planeet Aarde' en 'De planeet Aarde aantrekken'. Hierbij gaat het om de werking van de zwaartekracht. De betekenissen van deze concepten verschillen. Aangetrokken worden door de planeet Aarde is immers iets anders dan de planeet Aarde aantrekken. De referentieverzameling van het eerste concept is de verzameling bestaande uit de planeet Aarde verenigd met de verzameling van alle objecten die aangetrokken worden. De referentieverzameling van het tweede concept is de verzameling bestaande uit de planeet Aarde verenigd met de verzameling van alle objecten die aantrekken. De referentieverzamelingen van beide concepten lijken gelijk omdat iets aangetrokken wordt dan en slechts dan als het aantrekt. Terwijl de refentieverzamelingen gelijk lijken te zijn, verschillen ontegenzeggelijk de betekenissen van beide concepten, zodat een tegenvoorbeeld tegen het identiteitscriterium van mijn semantisch argument gevonden lijkt. Toch is van een tegenvoorbeeld geen sprake. Zo zijn er bijvoorbeeld virtuele deeltjes met een levensduur die zo kort is dat zij niet in staat zijn om tot een werkelijke manifestatie van aantrekking te komen, terwijl ze ondanks hun korte levensduur desalniettemin beïnvloed worden door het zwaartekrachtsveld waarin ze zich tijdens hun bestaan bevinden. Dit soort virtuele deeltjes behoren dus tot de eerste en niet tot de tweede referentieverzameling. Maar dan zijn zowel de betekenissen als de referentieverzamelingen van beide concepten verschillend, zodat van een tegenvoorbeeld geen sprake is. Dit laat echter onverlet dat Leo's voorstel een bijzonder fraaie en vernuftige poging betreft om tot een geslaagde weerlegging van mijn semantisch argument te komen.

Gisteren besprak ik uitgebreid mijn semantisch argument met Joop Leo van de afdeling Formal Semantics & Philosophical Logic van het Institute for Logic, Language and Computation in Amsterdam. Het was een mooi gesprek waarbij naast mijn semantisch argument ook de Tractatus van Wittgenstein de nodige aandacht kreeg. Zo besprak ik mijn eerder op dit blog uitgewerke interpretatie van Wittgensteins voorwerpen en atomaire feiten. Leo stelde vervolgens een fascinerend tegenvoorbeeld tegen het identiteitscriterum van mijn semantisch argument voor. Beschouw de concepten 'Aangetrokken worden door de planeet Aarde' en 'De planeet Aarde aantrekken'. Hierbij gaat het om de werking van de zwaartekracht. De betekenissen van deze concepten verschillen. Aangetrokken worden door de planeet Aarde is immers iets anders dan de planeet Aarde aantrekken. De referentieverzameling van het eerste concept is de verzameling bestaande uit de planeet Aarde verenigd met de verzameling van alle objecten die aangetrokken worden. De referentieverzameling van het tweede concept is de verzameling bestaande uit de planeet Aarde verenigd met de verzameling van alle objecten die aantrekken. De referentieverzamelingen van beide concepten lijken gelijk omdat iets aangetrokken wordt dan en slechts dan als het aantrekt. Terwijl de refentieverzamelingen gelijk lijken te zijn, verschillen ontegenzeggelijk de betekenissen van beide concepten, zodat een tegenvoorbeeld tegen het identiteitscriterium van mijn semantisch argument gevonden lijkt. Toch is van een tegenvoorbeeld geen sprake. Zo zijn er bijvoorbeeld virtuele deeltjes met een levensduur die zo kort is dat zij niet in staat zijn om tot een werkelijke manifestatie van aantrekking te komen, terwijl ze ondanks hun korte levensduur desalniettemin beïnvloed worden door het zwaartekrachtsveld waarin ze zich tijdens hun bestaan bevinden. Dit soort virtuele deeltjes behoren dus tot de eerste en niet tot de tweede referentieverzameling. Maar dan zijn zowel de betekenissen als de referentieverzamelingen van beide concepten verschillend, zodat van een tegenvoorbeeld geen sprake is. Dit laat echter onverlet dat Leo's voorstel een bijzonder fraaie en vernuftige poging betreft om tot een geslaagde weerlegging van mijn semantisch argument te komen.

zondag 7 juli 2024

Een nieuw Godsargument vanuit niet-bruutheid - column voor filosofisch tijdschrift Sophie (2024-3)

In wat volgt ontwikkel ik een nieuw Godsargument. Het vertrekt vanuit de premisse dat het feit dat deze wereld er is geen bruut feit is. Er moet dus een ultieme reden voor het bestaan van deze wereld zijn waarin elk verder waarom vragen tot rust komt. Deze reden moet daarom in absolute zin zelf-evident zijn. Ze moet anders gezegd in alle mogelijke werelden vanuit ongelimiteerd perspectief zelf-evident zijn. Voor het absoluut zelf-evidente maakt het immers niet uit welke mogelijke wereld actueel is. Nu kan iets alleen vanuit een bepaald perspectief zelf-evident zijn indien het mogelijk is dat een bewust wezen met dat perspectief inziet dat het zelf-evident is. Want het zelf-evidente verwijst naar een epistemische houding ten opzichte van zichzelf. Zelf-evidentie is dan ook net zoals betekenis fundamenteel relationeel. Als een reden zelf-evident is, dan is het dus mogelijk denkbaar als zelf-evident. Als het onmogelijk als zelf-evident gedacht kan worden, dan is het ook niet zelf-evident. Mogelijk gedacht kunnen worden als zelf-evident behoort tot de aard van zelf-evident zijn. Meer specifiek kan iets alleen in absolute zin zelf-evident zijn indien het mogelijk is dat een bewust wezen inziet dat het in absolute zin zelf-evident is. Maar een wezen dat inziet dat iets in absolute zin zelf-evident is, moet zich op de plaats van het absolute bevinden en een absoluut perspectief op de werkelijkheid hebben. Er is dus een mogelijke wereld waarin een bewust wezen zich op de plaats van het absolute bevindt en een absoluut perspectief op de werkelijkheid heeft. En omdat dit absolute wezen totaal onafhankelijk is en dus niet door iets anders is veroorzaakt, bestaat het in alle mogelijke werelden, waaronder de actuele wereld. Er bestaat dus in de actuele wereld een bewust wezen dat zich op de plaats van het absolute bevindt, een absoluut perspectief op de werkelijkheid inneemt, de ultieme reden voor het bestaan van deze wereld kent en inziet dat deze reden in absolute zin zelf-evident is. Dit absolute wezen kan met recht God genoemd worden, zodat volgt dat God bestaat. De premisse dat er een ultieme reden voor deze wereld is, is alleszins redelijk, zodat het ook redelijk is om te denken dat God bestaat. In elk geval laat mijn Godsargument zien dat er zonder God geen ultieme reden voor het bestaan van deze wereld is. En dit is hoe dan ook problematisch voor atheïsten die menen dat zo’n ultieme reden bestaat.

In wat volgt ontwikkel ik een nieuw Godsargument. Het vertrekt vanuit de premisse dat het feit dat deze wereld er is geen bruut feit is. Er moet dus een ultieme reden voor het bestaan van deze wereld zijn waarin elk verder waarom vragen tot rust komt. Deze reden moet daarom in absolute zin zelf-evident zijn. Ze moet anders gezegd in alle mogelijke werelden vanuit ongelimiteerd perspectief zelf-evident zijn. Voor het absoluut zelf-evidente maakt het immers niet uit welke mogelijke wereld actueel is. Nu kan iets alleen vanuit een bepaald perspectief zelf-evident zijn indien het mogelijk is dat een bewust wezen met dat perspectief inziet dat het zelf-evident is. Want het zelf-evidente verwijst naar een epistemische houding ten opzichte van zichzelf. Zelf-evidentie is dan ook net zoals betekenis fundamenteel relationeel. Als een reden zelf-evident is, dan is het dus mogelijk denkbaar als zelf-evident. Als het onmogelijk als zelf-evident gedacht kan worden, dan is het ook niet zelf-evident. Mogelijk gedacht kunnen worden als zelf-evident behoort tot de aard van zelf-evident zijn. Meer specifiek kan iets alleen in absolute zin zelf-evident zijn indien het mogelijk is dat een bewust wezen inziet dat het in absolute zin zelf-evident is. Maar een wezen dat inziet dat iets in absolute zin zelf-evident is, moet zich op de plaats van het absolute bevinden en een absoluut perspectief op de werkelijkheid hebben. Er is dus een mogelijke wereld waarin een bewust wezen zich op de plaats van het absolute bevindt en een absoluut perspectief op de werkelijkheid heeft. En omdat dit absolute wezen totaal onafhankelijk is en dus niet door iets anders is veroorzaakt, bestaat het in alle mogelijke werelden, waaronder de actuele wereld. Er bestaat dus in de actuele wereld een bewust wezen dat zich op de plaats van het absolute bevindt, een absoluut perspectief op de werkelijkheid inneemt, de ultieme reden voor het bestaan van deze wereld kent en inziet dat deze reden in absolute zin zelf-evident is. Dit absolute wezen kan met recht God genoemd worden, zodat volgt dat God bestaat. De premisse dat er een ultieme reden voor deze wereld is, is alleszins redelijk, zodat het ook redelijk is om te denken dat God bestaat. In elk geval laat mijn Godsargument zien dat er zonder God geen ultieme reden voor het bestaan van deze wereld is. En dit is hoe dan ook problematisch voor atheïsten die menen dat zo’n ultieme reden bestaat.Soφie is een filosofisch tijdschrift dat zesmaal per jaar verschijnt. Zij biedt een intellectuele uitdaging door kritisch na te denken over actuele onderwerpen, geïnspireerd door de christelijke traditie.

Labels:

Godsargument,

Sophie,

ultieme reden,

zelf-evidentie

dinsdag 2 juli 2024

Dasein is mogelijk-zijn

Volgens Heidegger is het Dasein zijn mogelijkheden. Dasein is altijd een kunnen-zijn. Het is als vooruit-naar-zijn steeds bezig in te gaan op ongerealiseerde mogelijkheden. Dit kan oneigenlijk worden geduid. Laat M de verzameling zijn van alle realiseerbare mogelijkheden voor een gegeven Dasein D en laat voor iedere m in M de kans dat D mogelijkheid m realiseert gelijk zijn aan p(m). Het wezen van Dasein D is dan { (m, p(m)) | m in M }. Deze oneigenlijke duiding van het Dasein als mogelijk-zijn verheldert niettemin de eigenlijke.

Volgens Heidegger is het Dasein zijn mogelijkheden. Dasein is altijd een kunnen-zijn. Het is als vooruit-naar-zijn steeds bezig in te gaan op ongerealiseerde mogelijkheden. Dit kan oneigenlijk worden geduid. Laat M de verzameling zijn van alle realiseerbare mogelijkheden voor een gegeven Dasein D en laat voor iedere m in M de kans dat D mogelijkheid m realiseert gelijk zijn aan p(m). Het wezen van Dasein D is dan { (m, p(m)) | m in M }. Deze oneigenlijke duiding van het Dasein als mogelijk-zijn verheldert niettemin de eigenlijke.

Labels:

Dasein,

Heidegger,

mogelijkeden,

oneigenlijk

Abonneren op:

Reacties (Atom)